We’re ready to discuss our final concept – acceleration – before diving into the mathematics of kinematics (what a mouthful!).

In the same way that velocity is a change in position over a change in time, acceleration is a change in velocity over a change in time. We’ve also got the concept of average acceleration () and instantaneous acceleration, in which

becomes vanishingly small, or “infinitesimal” in size.

Acceleration is, of course, something we’re all familiar with – most likely from experiences riding in a car or on a bus. The thing that I find really interesting about velocity as compared to acceleration is that if you were to block out all of your senses (and travel in an airless chamber), you would not be able to differentiate your traveling at an unchanging (or “constant”) velocity from sitting still, but you would be able to sense a (nonzero) acceleration*. Remember this: we sense accelerations (changes in velocity); our bodies don’t sense (constant) velocities! We will come back to this idea when we talk about forces.

Since acceleration is the change in velocity, and velocity is the change in position, and position is a vector, acceleration must also be a vector. Likewise we can get the units of acceleration by thinking about the units of velocity (m/s) divided by units of time (seconds), or .

Since acceleration is a vector, we need to talk about what it means when it is positive and negative, which can get a bit confusing. It is really really tempting, but completely incorrect, to say that a positive acceleration always means you are speeding up and a negative acceration always means you are slowing down. THIS IS NOT TRUE. I can’t emphasize this enough as it is a very common misconception when you’re first learning physics. I think this is partly because we usually don’t talk about forces until after we talk about kinematics, since forces explain motion and kinematics simply describes motion. However, I think it is easier to visualize whether or not an acceleration is causing an object to speed up or slow down if you have the aid of the concept of force.

A force is simply a push or a pull. That’s it. Forces can be caused by a lot of different phenomena, but we’ll talk about that later. Right now, you just need to know that a force is a push or a pull, and that if you consider all of the forces acting on one object, or the “net force” acting on that object, you will find that the net force is proportional to** the acceleration of the object, or mathematically, . (Note that this is a vector equation, and it implies that the direction of the net force is the same as the direction of the accleration.) To make this as clear as possible right now, we’re only going to imagine a single force acting on our object. Thus if I push my object to the right (in the positive direction), its acceleration vector points to the right (it has a positive acceleration). If I push it to the left (in the negative direction), its acceleration vector points to the left (it has a negative acceleration. We might sum this up by saying that accelerations are the results of forces.

So, now that we’ve clarified the conditions for when an acceleration vector points in the positive vs. negative direction, we can talk about how we can determine whether we’re speeding up or slowing down. The key is that to determine whether an object is speeding up or slowing down, we must compare the direction of the acceleration vector to the direction of the velocity vector. If they point in the same direction, the object is speeding up; if they point in opposite directions, the object is slowing down. I like to think of it as, “The object speeds up if the acceleration reinforces the velocity, and it slows down if the acceleration opposes the velocity.” And this makes sense because the direction of the accleration is the direction of our force: if my object is moving to the right and I push it to the right, it will indeed speed up. If my object is moving to the right and I push it to the left, it will slow down.

Here’s a drawing of the vector direction possibilities and whether or not they correspond to speeding up or slowing down:

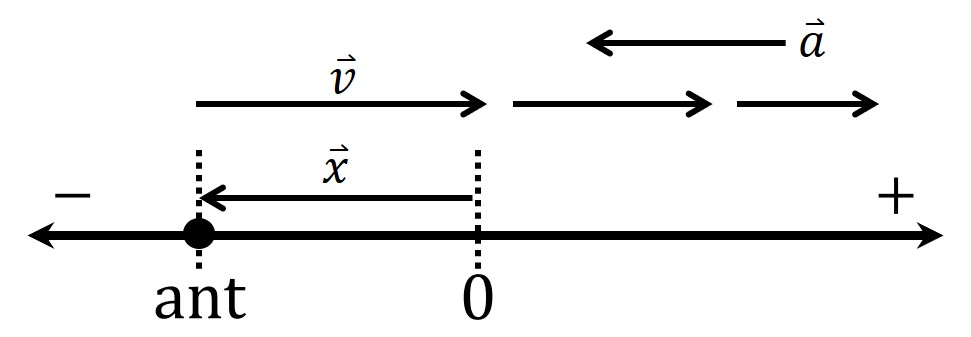

Finally, let’s draw all of our vectors together (position, velocity, and acceleration). First, an example, and then you’ll try it on your own.

For our example, we’ll draw a sketch of an ant that has a positive position, is moving to the left, and is speeding up.

I’ve drawn several velocity vectors with magnitudes (lengths) that increase as we move to the left to indicate to myself that the velocity is increasing to the left over time. (The object is speeding up to the left.) Since the arrows are getting longer, the acceleration must be helping the velocity, and therefore it also points to the left.

Now you try: draw a sketch of an ant that has a negative position, is moving to the right, and is slowing down.

And that’s it! We’ve finished establishing the concepts of position, velocity, and acceleration, including how we can represent them pictorially. We’re actually going to go back to algebra next week, with a guest post from my dad, and then we’ll dive into the kinematics equations!

* I’ve included some conditions in parentheses here so that I don’t get in trouble with the physics gods. In science, we always have to be very precise about the conditions for the situation we are considering; we can’t make any definitive statements otherwise. In physics, we tend to simplify the situation as much as possible by getting rid of as many inputs as we can***. In the case of blocking out all of your senses, someone might argue that you could still tell you’re moving based on the flow of air around you (though we could argue back that our statement includes blocking that sense of air flow) – so we put you in an airless chamber to emphasize that we’re ignoring the effects of the air. (Why not just say “ignore the effects of the air” and get on with it? Because sitting in an airless chamber is a more fun visualization of course! Or at least, that’s what most physicists would probably say.)

** “Proportional to” is our fancy math way of saying “this variable equals a number times that variable.” So, for example, if our variable is proportional to our variable

, we could write

, where

is some unspecified number, or we could write

.

*** I think one of the things that people find confusing about physics is that it’s actually very challenging to set up the “simple” situations physicists like to consider. This seems to be a hold-up sometimes: the non-physicist is stuck on how to make it happen while the physicist just says, “We won’t worry about the steps it would take to make this condition true in reality; we’ll just say that it is true and think about what that means.” This is also one of the reasons many experiments are so challenging: in our volatile world, it is very hard to isolate objects in different ways to break down the effects of various influences. (Case in point: try to get rid of friction.)