One of the things we talked about in my last post was velocity, , which is defined as the change in postion of an object over the corresponding change in time, or

.

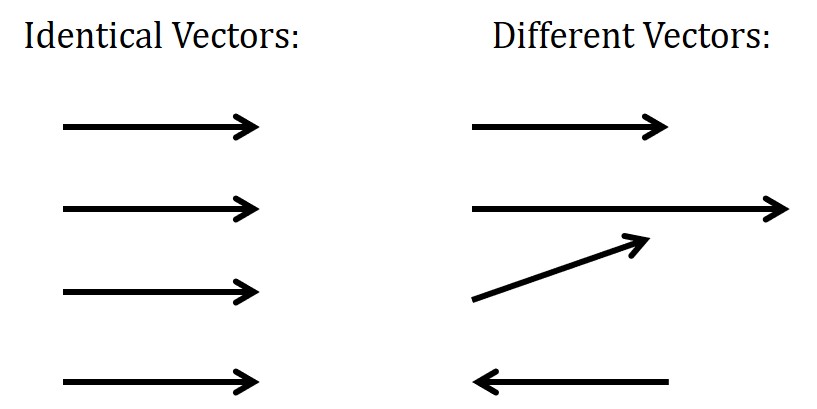

As was the case with position, velocity is a vector. Since a vector has both magnitude and direction, it makes the most sense to draw it as an arrow. (You may even be seeing an arrow in your head every time I say the word “direction.”) The length of the arrow pictorially represents the magnitude of the vector (how big is the number?), and it points in the direction of the vector. This means that two vectors are identical if they point in the same direction and have the same length.

That third vector down on the right is actually a two-dimensional vector (how’d that get in there?), which we will talk about in a future post. But for now, we’ll stick to one dimension – in particular, a horizontal line.

Now that we understand how to draw a vector in general, we can talk about the specifics of position and velocity vectors. Both position and velocity vectors (and any quantity described as a vector) will look like arrows. Labels help us differentiate position vectors from velocity vectors, but even more important is understanding what the direction of the vector means. A positive position vector tells us that an object is located on the positive side of zero*; a negative position vector tells us that an object is located on the negative side of zero. In contrast, a positive velocity vector tells us that an object is moving towards the positive direction, while a negative velocity vector tells us that an object is moving towards the negative direction. Note that in these statements, positive velocity vectors are not tied to positive position vectors, nor are negative velocity vectors tied to negative position vectors. Velocity vectors merely point in these respective directions to indicate the direction the object is moving.

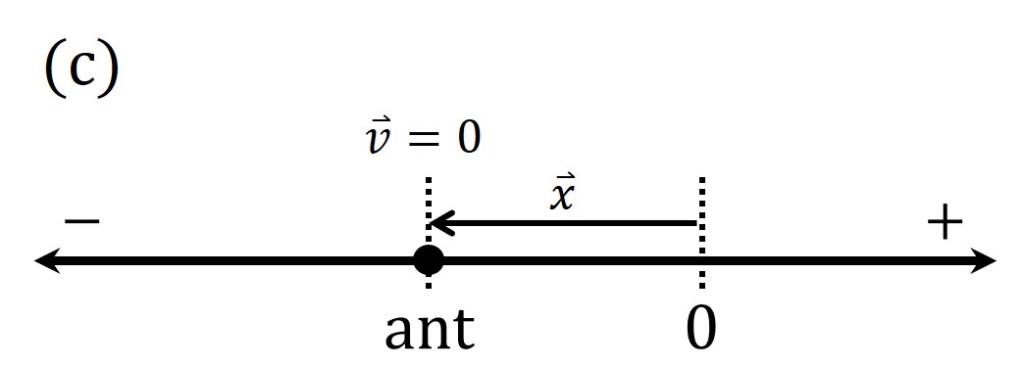

Let’s take a look at a pictorial example. In the picture below, the dot represents our object. Let’s go back to the ant walking along the crack in the sidewalk from a few posts ago. This picture depicts a snapshot in time, showing us where the ant is located and how fast it is moving right at this instant. Based on the picture, we would say that the ant has a positive position vector and a negative velocity vector. That is, the ant is located to the right of zero but moving to the left:

Now you try! (a) If I tell you the ant has a negative position and a negative velocity, what picture would you draw? (b) What about if the ant is located at zero and has a positive velocity? (c) What about an ant with a negative position and zero velocity?

Those zero ones are a bit of a trick: you can’t draw a vector of length zero! Instead, we simply label the position(velocity) as zero in our diagram.

Hopefully you are now starting to get comfortable visualizing the position and velocity vectors associated with the object you’re studying**. This means we’re ready to start thinking about acceleration vectors.

*Note that the positive and negative directions are arbitrary (except for the condition that they point opposite of each other). This fact allows us to make convenient choices for mathematically representing physics problems, as we’ll see, but there is an assumed standard unless otherwise indicated: horizontally, to the right of zero is positive and to the left of zero is negative, while vertically, up from zero is positive and down from zero is negative.

**You’ll benefit greatly from practicing visualizing a physical situation and then translating it into a representative sketch, indicating and labeling important quantities (such as the position and velocity vectors). I almost always begin solving physics problems by drawing a sketch of some sort. It helps me get what’s in my head onto the paper so that I don’t have to hold everything in my mind while I solve the problem. I cannot stress enough how critical a skill this is for learning physics.