There are a lot of ways to go about teaching physics. We could start by talking about energy, or forces, or the fancily named “kinematics” – and there are various arguments for choosing each of these approaches. Starting with kinematics is probably the most standard approach, and it’s the approach I’m going to use in this blog.

I like starting with kinematics because it starts with the simplest experiments for us to do, asking the question, “What is the math that describes motion?” We’re not talking about why motion happens yet; we’re just stating our observation that it does indeed happen and we’d like to write something definitive about it. So that’s where we’ll start: describing motion, or “kinematics.” In time we’ll start to explain why motion happens, the study of which is called “dynamics.”

The most obvious question to ask about an object is, “Where is it?” (And how do we describe its location mathematically?) This is what we call the “position” of an object: its location in physical space. But there’s a catch! In order to state where something is, we need to have a reference point. Saying that “My phone is 10 cm” doesn’t make any sense; this is why we add “away” onto the end, saying instead, “My phone is 10 cm away.” But away from what? Implicit in this statement is that my phone is 10 cm away from me, because that’s how the English language works. But in physics, we can’t settle for being implicit, because that inevitably leads to misunderstanding and confusion. Instead, we need to be very explicit, always clarifying our reference point.

We call our reference point the “origin” of our “system.” What’s a system you ask? It’s basically all of the obejcts we’re considering. I could talk about the “system” of my laptop, my phone, and my mouse. Perhaps I decide to use my mouse as the reference point – the origin – of this system. I could then tell you how far away and in what direction my laptop and phone are from this origin, and you’d know how my desk looks*. So to measure position, we must define an origin – a place from which all of our measurements will originate. This means that the origin is our zero point.

Ok, back to position. Position has units of length – such as meters – and, as we’ve established, it tells us where something is relative to our zero point. As great as it is to sit and stare at a motionless object (oh, we’ll get there!), we started our discussion by talking about motion. So let’s have our object move. And to simplify our discussion right now, we’ll only let it move in one dimension – that is, along a straight line. For example, we could think of a (straight) crack in the sidewalk and an ant walking back and forth along the crack. The ant would be in one-dimensional motion. If we pick an origin, we can then describe where our ant is at any point in time**.

So here’s our line with our origin:

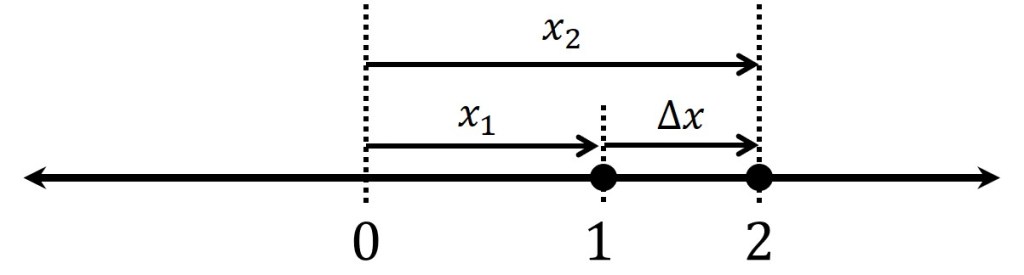

Let’s say the ant moves from point 1 to point 2. We need a way to label the positions of these two points, and for that we’ll use the letter . So point 1 is

meters to the right of the origin, and point 2 is

meters to the right.

Now say I want to describe the ant’s change in position. “Change in” means “subtract one value from the other,” and we denote this operation with the Greek letter capital delta, . So the mathematical statement

is our short-hand for saying, “The change in the ant’s position is its final position,

, minus its initial position,

.” (This is why math is so great! It allows us to communicate a ton of information in very few symbols.)

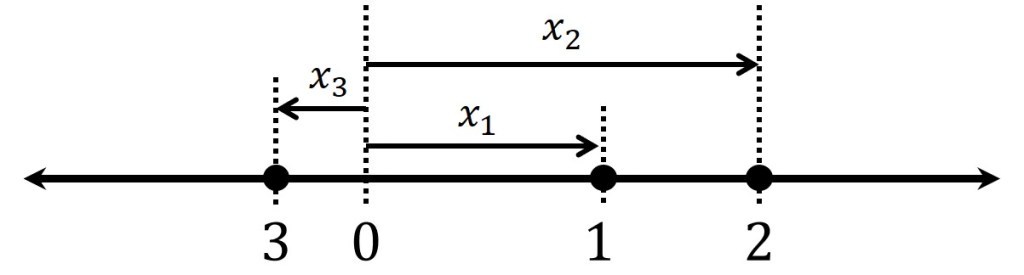

We call this change in the ant’s position () the “displacement.” This is a very particular term! It is not automatically the same as the total distance traveled by the ant. (Displacement and distance traveled can be the same numerical value, but they are not automatically so.) In the image above, it just so happens that the displacement is identical to the distance traveled by the ant. But let’s add a third point to our line:

Now say the ant travels from point 1 to point 2 and then turns around to head back to point 3, which is to the left of the origin. Let’s give ourselves some numbers so that we have something concrete to think about. We use the convention that numbers to the right of the origin are positive and numbers to the left of the origin are negative. How about we say that ,

and

. The displacement is the final position (

) minus the initial position (

):

. What this is telling us is that the ant’s final position is 0.4 meters to the left (in the negative direction) from its starting position at point 1. In contrast, the total distance traveled is the distance from

to

(0.2 meters), plus the distance from

to

(0.6 meters) for a total of 0.8 meters. Notice that in calculating the total distance traveled, we are only using positive quantities, whereas in calculating the displacement, the sign of the position mattered. We’ll return to this in a future post.

Ok: now it’s your turn! Let’s say the ant starts at point 3 (), walks to point 2 (

), and then turns around to walk back to point 3, where it stops. What is the ant’s displacement? What is the total distance traveled by the ant?

In this example, we find the interesting result that we can travel a long distance without experiencing a displacement: when we end exactly where we started, our displacement is always 0. (We moved 0 meters from our starting point.) Again, this gets at the fact that for displacement, the sign of the position measurement matters, while for total distance traveled, we just have a number (1.2 meters). This is because position (and by extension, displacement) is a vector: it has magnitude (size) and direction ( or

), while total distance traveled is a scalar (a number without a direction attached to it). Mathematically, we indicate vectors with little arrows over the variable, so displacement would be written as

, where I’ve switched the subscripts to the more generic

(final) and

(initial) labels.

In the next post we’ll continue our discussion of vectors (honestly, they’re never going away) and add a new concept to the mix: velocity.

*You might be asking yourself, “That’s great that I know where her phone and laptop are (in relation to her mouse), but where is her mouse located?” And to answer that I would need to give you a new reference point – perhaps I could tell you where my mouse is in relation to myself. But where am I? You can see that this will go on forever; there’s no absolute origin for everything in the universe. This should actually make you very happy: it means that you get to pick the origin that is most convenient for your measurements. We’ll explore this freedom as the blog progresses.

**Of course, to measure time, we have to again have a starting point from which to measure it. While we could measure all times from the inception of the universe (the Big Bang), this is massively inconvenient and entirely unnecessary. Let’s just say I have a stopwatch and we’re measuring all times from when I hit “go.”