This post is all about math, because in order to go beyond purely conceptual physics, you need to be comfortable with mathematics. It’s how physicists talk to each other; it’s the language of physics.

So, what math skills do you need to successfully follow this blog? Since I’m starting out with algebra-based mechanics, you definitely need to be comfortable with algebra. You also need to know your way around a right triangle. However, since this is not a math blog, I’m not going to try to teach you math in this post – but I will remind you of a few things.

Right Triangles

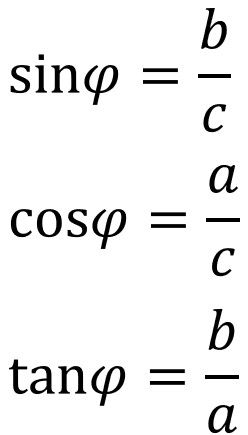

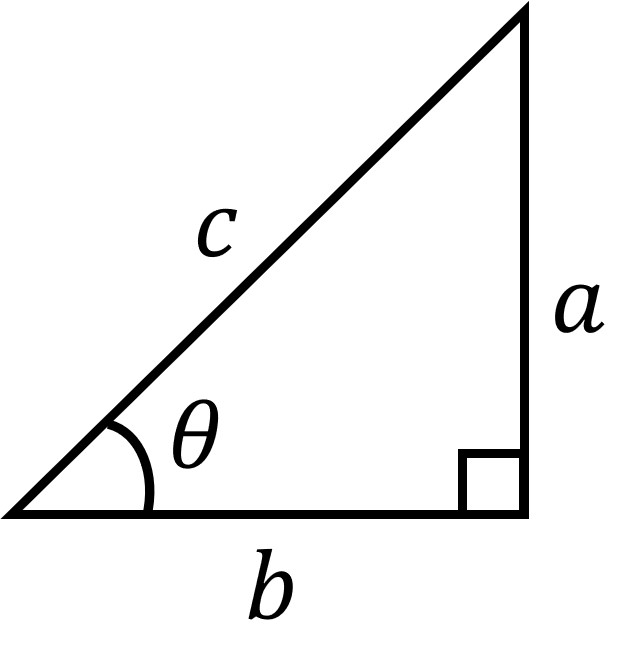

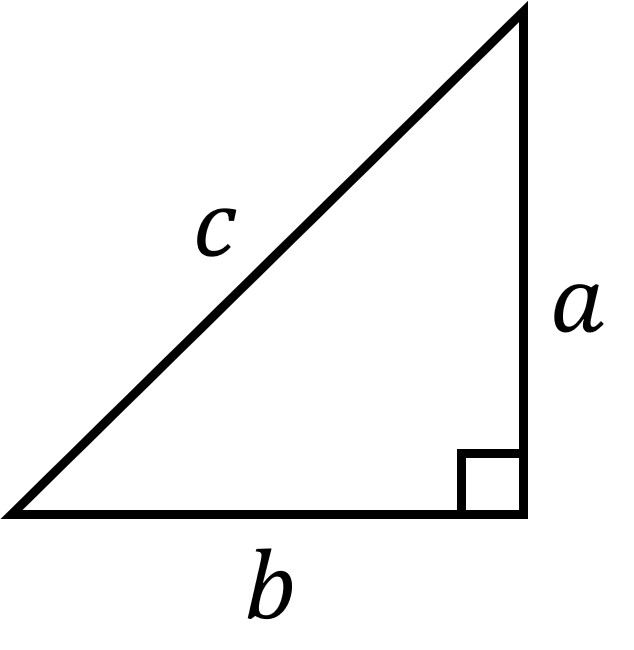

When it comes to right triangles, it’s basically about your trigonometric (trig) functions. Here we just care about the “Big 3” – sine, cosine, and tangent. These functions are all defined in relation to a given angle in the right triangle. In the triangle below, we’ll label the lower left angle with the symbol , the Greek letter “theta,” and we’ll label all of the sides of the triangle in relation to

:

Notice that the “adjacent” leg of the triangle is next to while the “opposite” leg of the triangle is across from

. The hypotenuse is always the side of the right triangle that is across from the right angle. You always want to think about sine, cosine, and tangent in terms of the opposite side, the adjacent side, and the hypotenuse. Given the triangle above, the trig functions are defined as

Now let’s use some variables to name the sides of the triangle. (A variable is just a letter that stands in for a number. We don’t specify what number, just that it’s some number.) We’ll use the letters ,

, and

. Based on the drawing below, we find that our trig functions are

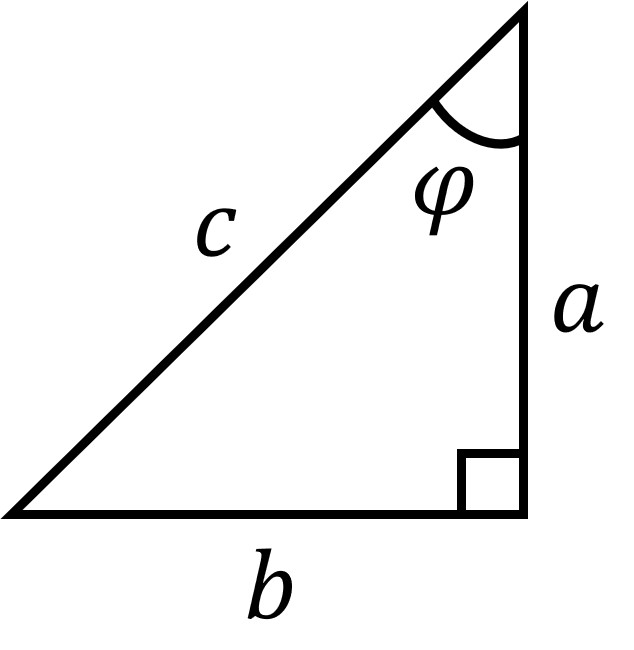

Ok, now let’s do a what-if (which is something physicists love to do): what if we pay attention to the upper angle instead? Let’s name it with a different variable , the Greek letter “phi,” as shown below:

What are the three trig functions in relation to the angle ? (If you’re reading this blog to learn physics, as opposed to reading it just to read it, try to answer this question yourself before looking at the answer below. Cheyenne’s got her eyes on you – she’ll know if you peek!)

Ok, great! Now let’s compare our functions of and

. Looking closely, we notice that

and

. This will always be true in any right triangle, period. It’s how right triangles work.

The last thing to remember about right triangles is that they follow the Pythagorean theorem. The sides of a right triangle as labeled below always obey the relationship

Algebra

When it comes to algebra, to succeed in physics, you need to be confident in manipulating equations and handling multiple equations at the same time. What do I mean by this? Well, let’s take a look at the following formula:

Right now we’re not going to worry about what the letters mean. (We’ll get to that as we learn more and more physics!) We’ll just accept that they each represent a different number, and see what we can do with them. Let’s solve for . This is shorthand for, “Following the laws of mathematics, let’s solve the equation so that

is by itself on one side of the equal sign.” Our steps would look something like

where I’ve listed the steps in gory detail in case it’s been awhile since you last studied algebra.

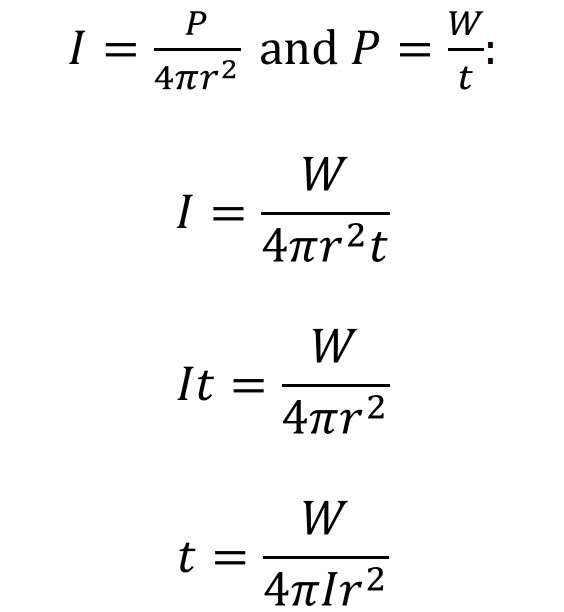

Now for a what-if: what if we’re told that ? Given our original equation and this new equation, can we solve for W? Let’s give it a try:

plugging the equation for into the equation for

:

Now a what-if for you to try! What if we solve for instead? Give it a try, and then check your answer below. (Sometimes I’ll post pictures of Chey, and sometimes I’ll use other pictures I’ve taken.)

Again, I’m posting every algebraic step in case it’s been awhile, but as you get more comfortable working with variables, you may be able to skip a few steps in your mind. For example, I’ve done so much math at this point that my mind can go smoothly and quickly from and

to

. But the way I got there was by thinking about every step when I was first practicing algebra.

In this blog, I won’t continue spelling out every single algebraic step, but I will try not to skip too many steps in one go when there is math to be done. You are always welcome to reach out to me if you don’t understand how I got from one line to the next in solving the math.

Finally, remember that if you have unknown variables, you need

separate equations in order to solve the problem. (Remember that

represents some number, so if we have 3 unknown variables, we need 3 different equations to solve the problem.)

And that’s about it for our review: right triangles, rearranging equations, and handling multiple equations with overlapping variables. You’ve got this – on to the physics!